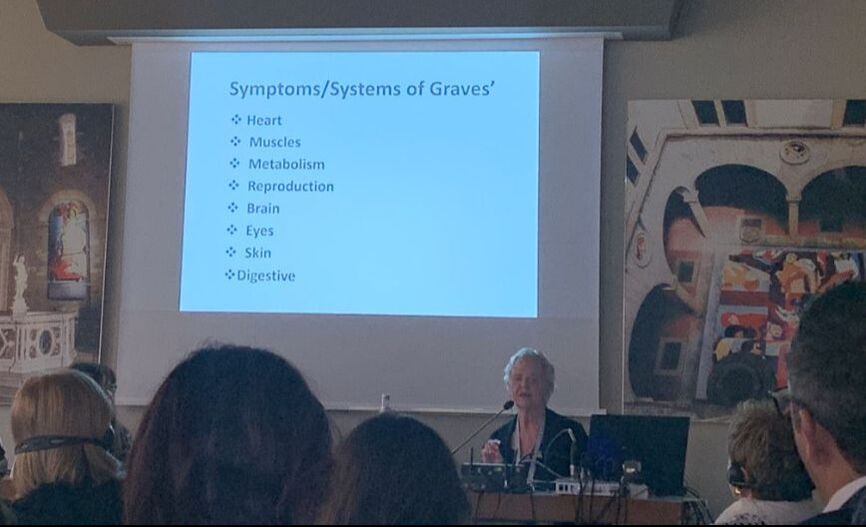

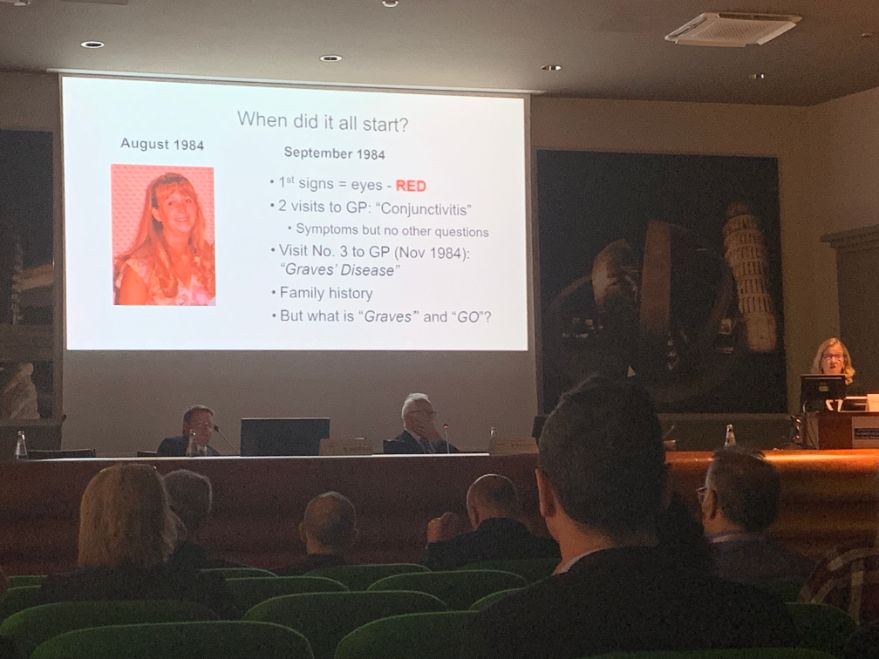

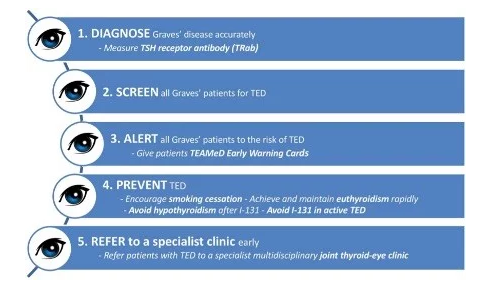

One foot in the Graves’Imagine waking up one day to realise you no longer recognise yourself in the mirror, your relationships are falling apart, you feel strange pains throughout your body and you feel a deep, heavy emptiness in your chest that nothing will shift. If you’re someone who has thyroid eye disease, you’ll know exactly what I mean. If you’re someone that knows someone that’s had it, you might know what I mean, but if you’re neither, the chances are you won’t. And that’s understandable, as it’s a rare disease. It’s also a complex one, in which the eye muscles, eyelids, tear glands and fatty tissues behind the eyes become inflamed. Often accompanied by anxiety and depression caused by fluctuating thyroid levels, and exacerbated by the change in appearance and other physical symptoms. As there is no cure, efforts are focused on effective resolution of the life changing symptoms. I have Graves' disease which, for me, caused both hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) and thyroid eye disease (TED). It wasn’t until my recent trip to EUGOGO Conference in Pisa, which I attended as a patient representative, that I realised how important it is that I share my story. I was lucky enough to attend the Conference on behalf of the recently formed Thyroid Trust, a patient-led charity for people affected by thyroid disease in the UK. EUGOGO is a consortium of clinicians (endocrinologists and ophthalmologists), clinical epidemiologists and radiologists, committed to improving the management of patients with Graves' Orbitopathy. My Story (The Abridged Version) Photo from Unsplash Photo from Unsplash As well as aching bones, shaking hands and increasing stomach complaints. Back in the nineties having mental health wobbles wasn’t something you tended to ring your mates about. It wasn’t something you were particularly honest with your doctor about either, as there was always this hovering fear that there was a straightjacket with your name on it not too far away. On describing my symptoms, I remember the nonchalant way the middle aged doctor avoided eye contact and told me he was prescribing me Prozac. In my early twenties, of all the drugs that I might have had an interest in, this wasn’t one, so the doctor reluctantly put me forward for therapy. I went with it, letting myself be convinced that my symptoms were all down to depression. I wasn’t surprised I was depressed, and I was pleased for the opportunity to get therapy. I’d suffered a fair amount of trauma in the subsequent years and knew I’d not dealt with it. But deep down I couldn’t believe that depression would be quite so physical. The trouble was, relentlessly trying to convince a doctor that common mental health symptoms are not ‘just’ a mental health problem is about as convincing as screaming “I’m not angry” in your partner’s face. After twelve weeks of therapy, I had the most excruciatingly embarrassing, devastating and unspeakable accident at work that I’ll spare you the details of. The people at work were kind, and I was given a change of clothes and sent to the doctors, where a female doctor listened to my panicked offering of worsening symptoms. The insomnia, the painful and unpredictable stomach and bowels, the ongoing weight-loss and strange bone pains. The tremors that had gotten so bad I found it hard to type. I worried I’d offended her in some way as she told me to “try to relax” with a straight mouth and furrowed brow. You try to relax when your bowels are in the habit of giving you an average three-minute warning of action and your skin feels like it’s stuffed with hyperactive worms nibbling their way through the muscle. Some days later, when even my skinny jeans were falling off my hips despite an insatiable appetite and my thoughts were burning through my skull, on a tearful, shakey and desperate visit to the GP, a young (different, again) doctor recognised my symptoms. Finally. He sent me straight to the hospital, where blood was taken and I was put in a cold, empty white room, and told to wait. Thank God. I’ve got a disease. I was delighted when I was diagnosed with thyroid disease. I had no idea what it was, but it sounded serious, and I felt like I was finally being listened to. I envisage a couple of weeks wired up in the hospital. Space to hide from the unkind world. But then, when they said that I could go home, take some tablets called Carbimazole and wait, I felt dejected and petrified. The following months were the worst of my life. My mental health plummeted and horrible, intrusive thoughts hammered at my sense of self, until I honestly believed I was evil. My face started changing shape. My soon to be ex boyfriend pointed out that my cheekbones had inverted. I’d also grown lower cheeks like a chipmunk, my throat was nearly as wide as my head, and my eyes were bulging, staring, with huge bags that made me look like I’d been beaten up but somehow avoided the bruising. Friendships started to fall apart. I was too deeply buried in my own head to participate in the world, and I’d always had a strong opinion but now people thought I was angry and arrogant. With my wide eyes staring, my hands shaking, who could blame them? And I was angry. As angry as I was scared and increasingly alone, as I pushed more and more people away. I wished I wasn’t alive, a lot. I didn’t want to kill myself because of the effect it would have on others, but I didn’t want to be alive. I eventually discovered that I was being overmedicated on the Carbimazole. An under-active thyroid can trigger or exacerbate depression and mood swings, which is likely to have been a huge part of how I felt. Or, perhaps it’s to be expected with my changing face and the trauma of my previous symptoms. Whatever the cause, it was worse than before, much worse: and I wouldn’t wish either on anyone. The Second Best Surgery EverOnce they’d sorted out my medication, they put me on urgent surgery to have my thyroid taken out. I was even pleased for the complications that kept me in hospital for a week, if I’m honest. It was like an escape from everything. I got to sleep all day on morphine. They also told me the good news after the surgery: “You don’t have cancer!” Of course this was great news, but also unexpected. I’d had no idea that the reason for the urgent surgery was because they’d thought I did and there wasn’t time to mess around with a biopsy. I was in pain, with tubes coming out of my neck, and I had to eat ten dry, chalky, calcium tablets a day to deal with a deficiency caused by the surgery, but nonetheless, I was happy. That is until I got home to the mirror and reality. I’ll come back to that later. Fifteen Years On: A Trip To PisaIn November 2019 I attended the EUGOGO Conference in Pisa as a representative of The Thyroid Trust and a patient of Graves' Disease and Hyperthyroidism. Just the invitation felt serendipitous, and I’ll forever be grateful to The Thyroid Trust for the opportunity.

He sorted my room out for me and told me about dinner at 8pm, which was a good job as I’d completely forgotten. Later, I dragged myself out of my hotel room and I joined the better-dressed-than-I-was crowd in the lobby. We walked to the restaurant in the rain and it was my first real look at the beautiful cobbled streets of Pisa. My hat protected my hair, just about, as others walked under their umbrellas. Everyone was in high spirits and my energy lifted too. The restaurant had long wooden tables and stone walls. At our table there were two Croatians, one Polish, three French and two English. It was a great crowd and the slight language barrier made it even more fun. Dinner was served and the courses kept coming, though the vegetarian options were limited, everyone made sure I got fed. As we slowly warmed to each other, the conversation got more and more energetic as the bottles of wine emptied. The EUGOGO ConferenceI woke up fresh and, after a quick coffee in the hotel restaurant, we made our way to the Camera di Commercio di Pisa (the Chamber of Commerce), which was in a small square in the center of Pisa and houses a patient information center. The building reminded me of a 1960s town hall with the deep echoing interiors and wide staircases that could have been anywhere, were in not for the large hung paintings and photos, to remind us we were in Italy. I shuffled in next to one of the Croatian ladies I’d gotten to know at dinner. Her friend was wearing a huge smile as she took a photograph of us together and I immediately felt I should be tweeting or something, but brushed the thought away. After some introductions from the front of the room in Italian and English to thank everyone for coming, we started. The first talk discussed the pathogenesis of Graves' Orbitopathy and was led by Dr Mario Salvi. As I tried to decipher the words filling my ears, it quickly became clear to me that I was going to struggle to understand what was being said. It’s hard enough to translate medical terms you’re unfamiliar without a headset translation against the backdrop of the speaker’s voice. I watched with admiration as my new friend, despite English being her second language, took copious notes, and I did my best. What is Thyroid Eye Disease?Dr Mario Salvi, talked us through the Pathogenesis (the medical term used to describe the development of diseases), Prevention and Natural History of Thyroid Eye Disease. Thyroid Eye Disease (TED), also known as Graves' Orbitopathy or Ophthalmopathy, is a rare autoimmune condition that has 2 stages: Active and Inactive. It will move through those stages in 18 months to three years. Therefore, it demands early recognition and intervention/treatment. It occurs when the body’s immune system attacks the tissue surrounding the eye causing inflammation in the tissues around and behind the eye. Muscle enlargement, increase in fat and inflammation of the tissues can cause lid retractions, protruding of the eyes, swelling, irritation, and restrictions in movement of the eyes. In most patients, and in my case, the same autoimmune condition that causes TED also affects the thyroid gland, resulting in Graves' disease. Graves' disease most commonly causes thyroid overactivity (hyperthyroidism) but can also rarely cause thyroid underactivity (hypothyroidism). TED can occur in people when their thyroid is overactive, underactive or functioning normally. It can also occur after treatment for Graves' disease. These symptoms can vary from painful to uncomfortable, and the physical manifestations of this can be life changing. Catching it early is everything. There is a carefully timed and structured procedure for the process of correction, which includes medication, radiotherapy and/or Thyroidectomy (the surgical removal of all or part of the thyroid gland, as I had) to balance hormones, followed by operations to remove fat, and orbital decompression if required. There were horrifying pictures of the disease at its worst, with the eyeballs threatening to pop out of the eye sockets. As I looked around the room, I saw many people with similar symptoms. My heart fell into my stomach with empathy, and guilt, as I was stung by the lack of gratitude for how lucky I’ve been. The memories started flooding back. Signs and symptomsBecause I was showing so many other symptoms, it wasn’t hard to diagnose, or at least I shouldn’t have been. I had bulging eyes, which were dry and sore most of the time, and it was hard to focus on anything. I also had a goiter (swollen neck), and as described before multiple physical symptoms of Graves'. However, this isn’t the case for everyone. Dr Angela Sframeli, from Pisa, described the development of the symptoms and the severity . Early signs

Warning signs

Danger signs

She explained that there are many other non-thyroid related illnesses that cause similar symptoms and protruding of the eyes. Examples include:

TED and Graves' are frequently misdiagnosed, meaning that doctors can often lose time in treating them effectively. In the early stages, TED is often misdiagnosed as conjunctivitis, which is especially problematic as this can take a long time to resolve, so TED could develop in the meantime. CausesAs Dr Salvi described the triggers for Thyroid Eye Disease, my story made a lot more sense to me. Along with Hypothyroidism and the duration of Hyperthyroidism being likely factors, smoking is something that came up again and again throughout the talks. Well, I smoked long before and throughout my illness, and for a number of years beyond it. I’m sure my surgeons will have told me the dangers, but that made no difference to me at the time. However, if I could go back to my twenty year old self and explain just how much of an impact the habit was having on my face, I’m sure it would have made a difference. Number one piece of advice to anyone who has Graves' (or anyone for that matter): Stop smoking. The Best Surgery In The WorldThe happiness that followed my thyroid removal was short lived. I hated the way I looked and I was starting to become confused about what was me, and what was the disease. I started to investigate plastic surgery to fix my eyes. I became obsessed with finding ways to return to my old self. I worked out how much I’d need on my credit card and I booked a visit to a plastic surgeon. Then the magic happened. My doctor told me I was a candidate for this procedure on the NHS and introduced me to Moorfields Hospital. I cannot describe to you the feeling of being understood after a journey of feeling so lost and helpless. When Surgeon Mr Jimmy Udin, told me that he would carry out the surgery for me, I felt the sun come back out in my head. First we would do the fat removal, and if that wasn’t enough we’d consider the other options. The fat removal surgery is carried out under local anesthetic. To give you an idea of what that’s like, just imagine lying on an operating table and watching someone use a scalpel to cut you. I’m not squeamish and it was actually pretty cool watching the surgeons do their thing. And of course the drugs will have played a part in my enjoyment. But then came the pain. A white, digging pain that shot through my lower lid into my cheek bone. I knew the drugs had worn off as I started to feel the stark cold air of the room. As I watched the knife glinting in the pure-white of the surgery room heading towards my face I cried out “wait wait wait! It hurts”. There were looks of mild panic all round but they calmed me down and somehow they did the last little bit and that was that. I woke up with bandages across my eyes and I was eager to see myself. It took a few days for the red and purple swelling to go down and reveal that, if it had made any difference at all, it wasn’t noticeable. I still looked like a very tired frog. So on my next visit to the hospital my heavy heart lifted as it was agreed that I could go in for the next step. It was called a bi-lateral orbital decompression and it was hardcore. But as I was about to learn, I was one of the lucky ones. It was the best surgery in the world. Timing Is EverythingThe disease needs to be caught and the thyroid needs to be stabilised, usually, through the use of drugs, in my case Carbimazole. Then some people will then go through radiation therapy. Others will have steroids. For some this removes the need for surgery. In my case, even though it had been caught relatively late, and surgery was the only option, it had at least been caught in time for the surgery to be effective. Until now, I’m not sure I’ve ever fully appreciated how lucky that was. Dependent on when the disease is detected, there are a range of surgical and non surgical treatments available: Standard Therapy (non surgical)

Surgery

As Roberto Rocchi explained in his talk, up next, if the disease is not caught within the active phase, through anti-inflammatory options (radiotherapy/steroids), then orbital decompression is the best solution. However, it’s not an option for everyone, and some people can live with the symptoms for the rest of their lives. A Nurse And Patient’s PerspectiveNancy Patterson, spoke of the quality of life impacts and the need for the individual, and their family, to be prepared and counselled through the event. Her talk brought the reality of the disease to life for me. All the way from America, Nancy took the event from tones of medicine that, for me, complicated the facts with terminology and stats that are hard to relate to an individual’s experience. In plain English, she explained that Graves' disease is an autoimmune disease that makes antibodies that target the thyroid, causing it to become overactive. Whilst in TED antibodies target the tissues around and behind the eyes, as well as the eye muscles. She explained that Graves' usually happens first, but TED may come before or after the onset of Graves'. My own experience felt validated in some way, and I’m sure others in the room felt the same way, as Nancy called out that essentially every system in the body is affected by the symptoms of Graves'. That’s the muscles, the mind, the heart, brain, reproductive and respiratory. She talked about some of the very real impacts on life that the disease has, reflecting my own experience of…

Symptoms of TED

Despite the picture she was painting of the painful nature of the disease on all levels, she made sure everyone knew that even if things aren’t caught in the active phase, there are advanced treatments/surgery that can still help. Nancy helped us to understand the needs of all of the people involved in the patient journey.

She talked about what each of these groups need in the journey: Patients need:

Physicians need:

She urged patients to remember that while dealing with an existence that is complicated by Graves' and T.E.D., we are not governed by them. “We need to look at our lives from a different perspective. We are quite able to blame everything on our illness. Instead, we need to take credit for what we can do, and what others have helped us do. We need to redevelop our ability to dream and hope” What The Patients Said, And What The Doctors Said Back:One patient called for empathy from doctors and for doctors to be better trained in psychological and emotional support. In response, an Italian patient spoke with passion saying that to have empathy is one thing, but it’s nothing without truly listening to what patients are saying. Applause filled the room. Someone then asked how we can educate doctors and ensure all professionals that are likely to come across patients are fully aware of the symptoms (e.g. ophthalmologists and of course endocrinologists, although the latter are well educated in identifying symptoms as it’s a connected disease). Patients wanted to know what doctors were going to do to increase awareness of the disease and increase funding for a cure. The doctors passed that back, and said they needed patient groups to raise the awareness of the importance of increased focus on the disease, as well as patients supporting other patients through the disease, as there is nothing like a lived experience to truly understand what someone is going through. The doctors also called for patients groups to do as much as they can to support doctors in raising this issue, including influencing at a political level. This is what makes organisations like The Thyroid Trust, British Thyroid Foundation, Thyroid Eye Disease Charitable Trust and Thyroid Federation International so important. Playing Doctors And PatientsOn the coffee break I found that all of my new friends were in separate groups, speaking their respective languages, so I sought someone English to speak to. I’m not particularly shy, but situations where we’re forced to mingle aren’t my thing. I’d rather hide behind a china cup, and pretend to do something on my phone, than start up a conversation. So, I hung around one of the tall poseur tables and I waited. My heart beat a little faster than normal and my skin felt a little out of place. Soon enough a group of three took up the spaces around me, clinking their coffees down and speaking animatedly about something that sounded like research. They were all in suits, all attractive and all totally oblivious to my presence. I spent a while trying to catch someone’s eye, and eventually just blurted out: ‘Well it’s nice to be surrounded by English speakers. But I still can’t understand a word.” They laughed lightly and asked what field I was in. It took me a while to know the answer to the question, wanting to describe my business and prove I was worthy to hold this space, but in this context I was a patient. “I’m here on behalf of The Thyroid Trust. I’m a patient”, I told them. They all looked at me and fell silent. They seemed confused. “You couldn’t tell!” The male doctor to my right said, breaking the awkwardness I was feeling. I smiled and asked where they were from. Canada, the women said. The men nodded. Then, after a swift compliment: “You must have good genes to have recovered as you have. You couldn’t tell you’re a patient at all” The doctor to my right left, distracted by a conversation with another fellow doctor who had appeared. He seemed a very serious man. I found myself somewhat confused. Do I have good genes? Isn’t Graves' Disease a genetic disorder? And I’d just learnt it was for life. So surely that means my genes are categorically troubled? Nonetheless I accepted the compliment and took a note to tell my mum later. The other two continued with questions. “Have you had a total thyroidectomy?” “Yes.” “That’s the target treatment these days. It’s the way to go.” “Seems so.” I replied. “Any eye surgery?” “Yes”, I explained. “I had eyelid fat removal and bilateral orbital decompression.” They looked a little closer, but not invasively, and said “your surgeon must be pleased.” Something I hadn’t really considered until that day but “yes” I said, “I guess he must be.” One of them asked where my operation was carried out and I told them Moorfields. “Oh, Jimmy Udin is here from Moorfields.” I felt a wave of something like excitement. “He was my surgeon!” I confirmed, as it all came flooding back. The local anesthetic eye surgery. Seeing the knife coming towards me. My panic as I felt the cold knife against my awakening flesh. His firm hand on my shoulder. My reality slowly woke up inside me. I hadn’t ever considered the positive outcomes of the surgery and how lucky I was. It always felt unfinished. As if I never quite returned to where I had been before the disease, but I’ll never be sure as to whether that’s in my head or a reality. We talked some more and I learnt that they got a lot through the sharing of information across doctors, with this kind of networking and learning forming a key part of their continuous development. It seemed, though, that the patient element was more of an unnecessary bonus. But positive nonetheless. The woman then politely excused herself, explaining to me that she wanted to speak to another key surgeon who she was hoping would speak at an event she was planning. The other doctor stayed. Anything else would have been awkward. Although to be fair to him he seemed genuinely interested. We talked about my experience as a patient. He told me that I should consider doing talks, as I am a symbol of hope for people who feel they will never return to who they were. That definitely got me thinking. Eight Operations And A National Charity: Janis HickeySpeaking of symbols of hope, after the break Janis Hickey, founder of the British Thyroid Foundation and patient, told us her story of living with Graves' from 1984 to 2009. She talked about the hurtful comments from strangers, the candid words from children and well meaning but painful comments of friends and family. I will always have a memory of a very good friend widening her eyes at me and shouting ‘why are you staring at me?’ shortly before our friendship fell apart, as I wasn’t present enough when she lost her mother and neither of us knew my behaviour (and angry stares) were caused by a disease. Janis explained that you are unable to look people in the eye as you once could. They might think you’re angry if you do, or scary. And if you don’t look them in the eye, trust is compromised. It’s very hard to remain in normal relationships when that happens, as I can attest to. As Janis talked through the impact the disease had on her life I wanted to walk up to the stage and hug her. It was as if she was telling my story and I hadn’t even realised just how much my 20s had been filled with relationship difficulties, low self-esteem and finding it hard to cope. Janis underwent eight surgeries to return to normality. Her journey was an exceptionally hard one and that was a big part of what inspired her to start the British Thyroid Foundation, when the Canadian equivalent made the suggestion. She finished by speaking on behalf of all patients and calling for more to be done to ensure a better experience for patients, including well informed GPs able to make accurate and speedy diagnoses and refer to specialists within a joint clinic, as well as accurate and clear information and access to the solutions for the support that patients need to negotiate this complex disease. Collaborating To Make Things BetterThe final talk introduced us to TEAMeD, Thyroid Eye Disease Amsterdam Declaration Implementation Group UK. The Amsterdam Declaration 2009 says that “TED can have a significant and negative impact upon the quality of patient’s lives and visual function. Delays in making a diagnosis of TED and initiating treatment are common. “TEAMeD-5”, a 5-point programme to promote better care for patients with, or at risk of, TED, was officially launched at the Society for Endocrinology BES meeting in November 2017. The British Thyroid Foundation and Thyroid Eye Disease Charitable Trust have agreed to jointly support TEAMeD and provide administrative support. It has been joined by multiple groups of medical professionals to improve the patient experience for people with Thyroid Eye Disease through putting in place measures to ensure patients have access to early diagnosis, appropriate treatment, skilled professionals and high standards of joint care from endocrinologists and ophthalmologists. They have created a Thyroid Eye Disease warning card which is used by doctors to identify the signs and symptoms. The thing that really struck me about TEAMeD was the focus on collaboration across charities and medical associations in the improvement of the patient experience which in my opinion and the opinion of The Thyroid Trust, is what we need for TED and beyond. As someone who has worked across sectors, including the NHS, I can attest to how very important collaboration is, and how necessary it is to break down barriers and become one force for change, fighting towards one goal. How It All EndedOn the last night, I went out for dinner with the patients from the night before and Janis and Nancy. This time we chose the restaurant and we had a really wonderful time. We talked about our lives, our experiences of living with the disease, and how our charities were doing what they can to make patients lives better. I don’t think any of us really wanted the evening to end when it did, but at the point of going our separate ways we promised to stay in touch. My second biggest takeaway from the conference is the importance of patient groups to get together and work collaboratively. My experience wasn’t a particularly bad case, from what I now understand, it was pretty representative of people who were diagnosed then. Which helped me to understand the extreme importance of all of these women, and the organisations they represent. Those of us who have had the disease need to work together to create one, global, voice to increase the awareness of the importance of early diagnosis. Patient groups are so important in helping families and friends of patients understand what their loved one is going through, and how they can be supportive (and patient). We need to support the education of doctors that treat TED and Graves' in the emotional and mental health impacts of the diseases. As we help achieve all of these things, we need to build and deliver a strategy for influencing change at a funding and policy level. My biggest takeaway, was, how lucky I am. For me, Thyroid disease never really went away, but my operations were completely successful and I lead a normal, happy and healthy life. I am so, so grateful that I was given that second chance back all those years ago, and my trip to Pisa makes me wonder how different life would have been if I’d have lived in a time before the surgical innovations that changed my life. This year is full of intentions and exciting plans, including creating a wonderful home and life with my new(ish) husband, working with some incredible charities, continuing research and taking action to make transformational change across the charity sector, completing my training as a life coach, starting to teach meditation, writing as often as I can, and continuing my psychotherapy studies. High on the full list, is a visit to see my surgeon, Mr Jimmy Uddin, to see if he’s impressed with his work and to thank him for making all of this possible.

Photography creditsWe are grateful to the following photographers on Unsplash for use of their original images to help illustrate this article: Marie Rouilly, Daria Shevtsoka and Emma Simpson.

The conference photographs were taken by Kelly. 29/10/2022 07:41:53 pm

A quick look at Grave's disease Comments are closed.

|

Thyroid FriendsThis blog is by members of Thyroid Trust Friends Network who have signed up to our Ground Rules and blogging guidelines. Please get in touch if you'd like to write something for possible publication on our site. Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

for everyone affected by thyroid diseaseMeetingsWe organise regular information and support meetings online and in person.

Click here for upcoming dates. We are a small independent charity. We receive no government funding and are reliant on donations for our income. Please support us.

PlEASE CONSIDER SUPPORTING OUR VITAL WORKThe donate button above takes you to a secure donation processing platform, JustGiving. Please contact us if you would prefer to make a direct bank transfer to donate via any other means, or if you are interested in volunteering.

|

|

Proud members of the following organisations

|

Proud to be in a charity partnership with:

|

With thanks to all our supporters, including:

|

Correspondence ADDRESS15 Great College Street, London, SW1P 3RX

The Thyroid Trust is also known as TTT and Thyroid Friends Network,

Registered Charity Number 1183292 Registered Address: 15 GREAT COLLEGE STREET, LONDON, SW1P 3RX Copyright asserted 2019 - Our consititution and all policy documents can be viewed on request. Read our Privacy Policy updated 23/5/18, . |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed